Let's Play The Legend of Zelda Series Until I Die! The Legend Of Zelda

In which I spend a few minutes admiring the spare, abstract beauty of this first installment before being almost immediately killed by a goddamn bat.

The Legend of Zelda

Released: 1986 (Famicom Disk System), 1987 (Nintendo Entertainment System)

For an epic fantasy series spanning decades, Zelda starts off on a suprisingly sedate note. The dreamy opening music, the image of a peaceful waterfall under a pink dawn-like sky, and the floral embellishments around the title feel more like the introduction to a romance story than a swashbuckling adventure. Only the sword onscreen hints at any action or violence to come, and even that has an elaborate rapier-style hilt that looks more Princess Bride than Lord of the Rings.

Development background

The game was developed as a launch title for the Famicom Disk System in Japan. Inspired by director Shigeru Miyamoto’s childhood wanderings in the woods around Kyoto, the developers set out to create a small world for players to explore with an unusual degree of freedom in approaching their ultimate goal. This ran in direct contrast to the linear experience of Super Mario Bros., which Nintendo was developing concurrently, and that running comparison between the two games informed a lot of the design decisions (something that we’d see again in the following decade on the Nintendo 64). Since the Disk System—and its ability to write data to game disks—never made it to the US, the developers had to get clever for the Western release. As a result, the NES version was the first cartridge game to use battery-backed memory to allow players to save their game.

The story

An opening text crawl gives us the basic overview: an evil prince named Ganon (originally spelled “Gannon”) and his army invaded the land of Hyrule and stole the Triforce of Power, a powerful ancient artifact with vaguely-defined uses. He’s also after the Triforce of Wisdom, but before he got his hands on it, Princess Zelda of Hyrule broke it into eight pieces and scattered it in hidden labyrinths around the land. Ganon captured her, and now only the reassembled Triforce of Wisdom can defeat the dark lord to save Zelda and all of Hyrule.

The manual offers a bit more detail on exactly how our player character Link entered the scene: Zelda sent her nursemaid Impa out into the dangerous wilderness to “find a man with enough courage to destroy the evil Ganon,” and ran into Link just in time for him to save her from Ganon’s henchmen. She explained the situation, and “burning with a sense of justice, Link resolved to save Zelda,” presumably without actually saying anything.

All of these basic plot elements will return over the course of the series (they all appear in some form or another in Breath of the Wild, currently the most recent major Zelda game). The biggest thing missing here is the Triforce of Courage, which rounds out the classic three-triangle design of the Triforce and cements the ongoing connection between Link, Zelda and Ganon. Otherwise, though, it’s impressive how much of the Zelda formula came into being right at the start. That includes a lot of the gameplay elements too, as we’ll see.

How far can I get before I die?

Not very! This is a game from the 1980s. They were hard.

I start things off on the right foot by giving my hero a suitably epic fantasy name.

(This game doesn’t use your name except as a way to mark your save, but later entries will sprinkle it throughout the dialog, allowing for a lot of goofy possibilities if you name your character “…uh…” or something similar.)

The game opens and I am standing in the middle of a field. Exits are to the north, west, and east. Near the north exit, the darkened mouth of a cave beckons me.

I take a moment to appreciate the way this game starts. With no preamble at all, we’re faced with four possible paths. Link is facing away from the viewer, and he’s pointing north, which is a subtle hint that our immediate goal lies in that direction—but the game is careful not to railroad us. Right from the start, we know we’re going to have to make our own decisions and be willing to explore.

(The manual offers quite a few hints, of course, including a small map that plainly shows you the entrances to the first two dungeons. But the game makes an effort to be self-contained in a way that few of it contemporaries even attempted).

Being the only black element on the screen, the cave entrance stands out as our obvious first choice. We descend into the darkness via some charming footstep sound effects, and are met with these famous words:

No one is alone with a sword in their hand! I take the weapon and head off into the wilds. Adventure awaits!

Rather than pretend I’m playing this for the first time (I played and beat the first quest about four years ago) I decide to head directly for the first dungeon. Or labyrinth, as this game calls it—a more evocative name for sure. I head north and east, passing out of the dense forest and into shrub-covered grassland. I think.

As with most games on the NES, Zelda requires a bit of imagination on the player’s part. There’s a lot more detail here than in, say, an Atari 2600 game, but it’s still hard to tell what’s meant to be a tree and what’s a bush, or just a green-colored wall. I think that’s part of the fun of the experience, and makes it feel more like a collaboration between designers and players, but I can’t always shake the feeling that I’m missing a little of what the developers had in their head.

The first few screens are a breeze as I fling my sword across the screen to take out the rock-spitting Octoroks that roam the screen randomly, but pretty soon I take a hit. Without full hearts, I’m reduced to just swinging my sword in front of me like a loser. This is an interesting mechanic that mostly disappeared from the series after the first game; it provides a nice early advantage, but becomes harder to rely on as the game goes on and you accumulate more heart containers. Dying in the game will always return you to three hearts (even though you can have up to sixteen slots) and it can take a long time to collect enough to take on serious enemies. This makes death pretty punishing by the late game, because (if you’re me) every time you start over, you have to wander around the overworld grinding for more hearts before you can have any hope of getting through whichever dungeon is currently kicking your butt.

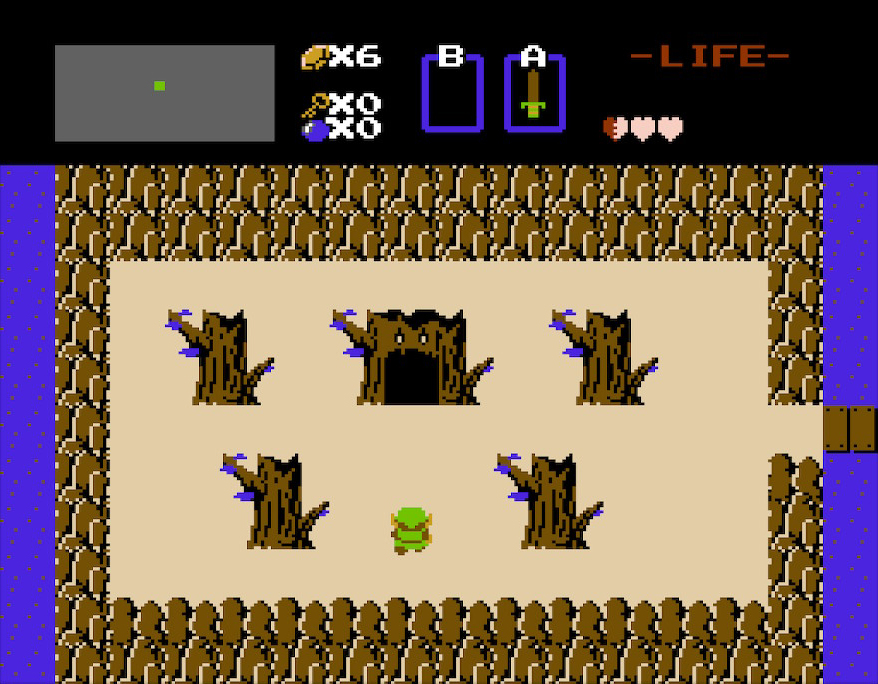

Fortunately, we don’t have that problem now because I’m only going to die once! And I very nearly do before I reach the first labyrinth, as a swarm of sand-burrowing Leevers block my way along a lake and Zora (or Zola, as they’re called here) fire spitballs at me from the water. I really don’t want this first outing to be that short, so I manage to fight my way across the narrow bridge and onto a rocky island ringed by spooky-looking dead trees.

How great is this entrance, by the way? So ominous, yet so irresistible. Even with the incredibly limited rendering capabilities of the NES, this manages an atmosphere worthy of the Dark Souls series.

I’m in bad shape. I only have half a heart left, and the game is beeping at me like a smoke alarm, which only makes it harder to focus (an annoying design decision that will be carried forward for most of the series). I’m going to have to summon all my courage and battle prowess to make it through the horrors that await me in the halls below. I take deep breath and enter the depths.

Then I get killed by a bat in the second room.

Sorry, not a bat, a keese. In Hyrule, bats are “keese”, snakes are “ropes”, giant carnivorous servings of flan are “like-likes.” It’s like visiting the UK, you get used to it.

Well, that was an ignominious beginning to my heroic quest. I didn’t time my playthrough here, but it couldn’t have been longer than five minutes. Following this up with the notoriously difficult Zelda II should be interesting!

Things I liked

I didn’t have much time to appreciate it, but there’s a lot to love in this humble first chapter.

- Starting the player off with so much freedom. The series wouldn’t be this open again until Breath of the Wild, over 30 years later.

- The developers manage to pull off a suprising level of variety among very simple enemies that move in random patterns, even in the first few screens.

- The sword-throwing-but-only-at-full-health mechanic.

- The fact that Nintendo clearly took inspiration from deep, complex top-down RPGs like the Ultima games and managed to strip down the experience to something vastly simpler and more accessible, while retaining much (if not all) of the sense of grand adventure.

- The music. In just a few beeps and boops, Koji Kondo managed to write a heroic theme that people would still be humming decades later as it passed down from game to game. I’m disappointed the eerie dungeon music never made another appearance in the series.

Things I disliked

- This game clearly came early in the life cycle of the Famicom / NES, which is to say its visuals are pretty lacking. Compare it to something like Crystalis, which came out four years later, and you can see how much more juice developers were able to squeeze from the 6502 processor once they’d had the time to optimize for it.

- Those stupid Zola spitballs somehow hit me every time. I have no idea why their aim is so good.

- The aforementioned beeping when you’re low on health. In the video above, you can see that it even overrides some of the music in the dungeon because of the limited audio capabilities of the system.

Was that a fair death?

Sure. The game overall is quite a bit harder than later entries would be, but I charged right at a group of enemies while mashing the attack button, and I deserved what I got.

Next up: one of the rare direct sequels in the series still manages to introduce a whole lot of convoluted timeline nonsense.