Let's Play The Legend of Zelda Series Until I Die! Zelda II: The Adventure of Link

In which I take on the black sheep of the franchise.

Zelda II: The Adventure of Link

Released: 1987 (Famicom Disk System), 1988 (Nintendo Entertainment System)

This game is easily the least-loved of the entire series, if we exclude the CD-i releases (but don’t worry, we’ll be covering those too). It took an intentional swerve away from the conventions established by the first game, introduced a whole bunch of new gameplay elements, and provided an experience that was less fun in almost every way. It’s also widely considered the hardest Zelda game, so this should be another brief run. It does have a lovely title screen, though, retaining the original’s serene mood while hinting at a greater and larger adventure. Instead of a blank pink sky we get a sparkling field of stars over a vast landscape (as vast as the NES could manage, anyway), and rather than decoratively flanking the title, the sword is now embedded directly in the cliff, outlined in orange as though blazing with its own light. What incredible adventures await us in Hyrule this time? Perhaps some aimless wandering that ends in a quick and pathetic death? We shall see…

Development background

The game was created by a separate team from the one that made the first Legend of Zelda and came out less than a year after its predecessor. Shigeru Miyamoto, credited under a pseudonym this time, apparently came up with the idea of making a side-scrolling action game with emphasis on high and low attacks, but doesn’t seem to have been closely involved with the project beyond that. Takashi Tezuka returned as the writer of the game’s story and script. Akito Nakatsuka took over for Koji Kondo as the composer, but none of his themes manage to stick with the series beyond this, and Kondo would shortly be back.

The story

Link (the one from the first game) discovers a mysterious mark on his hand shaped like the Triforce and learns from Impa (the one from the first game) that this is a sign that he is destined to find the Triforce of Courage, which will give him the power to break the spell of eternal slumber cast on Princess Zelda (not the one from the first game). The Zelda we rescued in the previous game is a descendant of this Zelda, the original from whom all female members of Hyrule’s royal family have since taken their names. Meanwhile, Ganon’s loyal followers have hatched a plan to revive their dark lord by hunting down his killer, Link, and then sprinkling Link’s blood on his ashes. This doesn’t seem to have anything to do with Link’s actual quest, it’s just happening at the same time.

The notion that there are many generations of Zeldas across the history of Hyrule is the first glimpse we get at the narrative approach of the whole series. Rather than follow the lives of specific characters, the games will instead focus on various iterations of Zelda, Link and Ganon at different points in history—a clever idea that will eventually devolve into the most convoluted chronology of any game series this side of Kingdom Hearts.

How far can I get before I die?

Longer than the first game—almost ten minutes! But I fail to even enter the first dungeon, so it’s a bit of a toss-up.

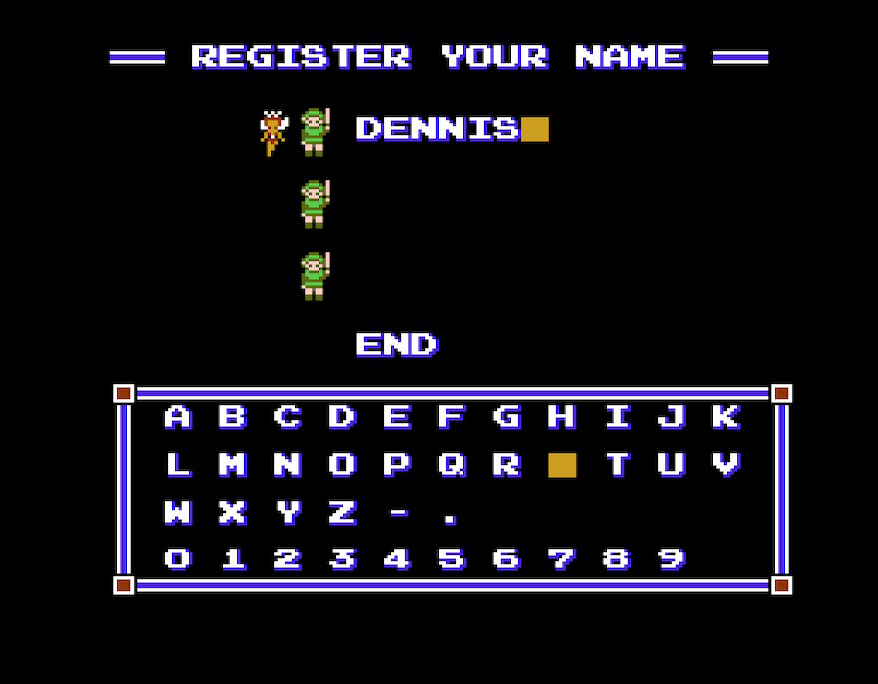

DENNIS rides again.

The game begins and I am standing in front of an ornate altar. The eternally-slumbering O.G. Zelda lies upon it. I’m impressed with the sprite work on Zelda here, which clearly indicates that her hands are folded together even from the side in such low detail. This would be an incredibly confusing place to start if you hadn’t read the manual (am I supposed to wake her up? Can I do anything besides stab at the air and jump?) but since I have, it’s obvious that I’m in the North Castle of Hyrule, ready to set off on my quest to return the six crystals to the foreheads of the statues in the six palaces so I can remove the “binding force” placed on the Valley of Death so I can enter the great palace and fight the last guardian and obtain the Triforce of Courage and awaken Zelda. And also not get killed, so Ganon doesn’t come back.

I exit the castle by moving to the right (moving to the left will also exit, because the way this game orients you in horizontal space is a little weird) and I find myself on the overworld map. Things look a bit more like the first game now, but that’s misleading. This map operates like a traditional RPG’s overworld map, in that I can only move from place to place until I enter a distinct location (a town, cave, or palace) or I get stopped in my tracks by a random monster encounter. As soon as that happens, I’ll be dropped back into the side-scrolling view and will control Link accordingly until I leave the area.

This is one of several RPG elements that the game introduces into the Zelda formula, the others including experience points, towns full of NPCs, and the ability to use magic. It was a bold move, and it paid off in its way, as a lot of these changes would stick around in future games (but not the overworld map. Or the experience points).

I’m not sure where to go exactly, so I wander around (avoiding monsters for the time being, who appear as blobby black-and-white icons) until I reach a town. The place is bustling, with NPCs walking around and going about their day, even entering and exiting from buildings. It’s a far cry from the first game, where the few NPCs are all standing motionless in one-room caves. It’s an impressive amount of detail for the NES, even if nearly all the villagers seem to be the same woman in different-colored dresses.

Talking to the villagers finally provides me with some guidance, although—as is typical for this era of gaming—the hints are vague and the text is agonizingly slow to appear on screen. It takes a while for anyone to give me any advice I can use.

I mean, sure.

Here we go. “Parapa,” I learn from the manual, is a desert located at the northeast tip of the game world, so I decide to head there. On the way, though, I finally get caught by a roving monster and the game drops me into the battle view. I’m standing with my sword at the ready, the combat theme music kicks into gear…and I see no monsters.

I have no idea if this is supposed to happen or not, but sometimes monsters just don’t show up. I walk across the empty stage for a little bit and then I’m back in the overworld, a little inconvenienced but no worse for wear.

I quickly find that a mountain range is blocking my path and a cave entrance offers the only way through. Before I can enter, I get pulled into combat again.

This time there are monsters—spiders dropping from the trees and this game’s version of Moblins (called Molblins at the time), which are burly pig-men who look a bit like miniature Ganons. The Moblins are throwing spears and I’m not feeling very confident just yet, so I take out one spider and hightail it out of the encounter, making my way to the cave.

No friendly bearded dudes with free swords this time. Instead, the cave is pitch black. I know from playing in the past that dark caves are full of enemies you can’t see, and that you need a candle to make them visible. I can’t remember where to get the candle, but it can’t be too far away, right?

I spend a while wandering the countryside before I start to worry that I missed something. I find another town in the mountains, and more dark caves, but the only other path—south of the town of Rauru that I first visited—is blocked by a massive boulder.

It occurs to me that, since I earn XP for killing monsters, I should probably stop avoiding them all the time. I’ve been hesitant to fight because I remember being really, really bad at the combat in this game in my past attempts. But maybe I just didn’t spend enough time out grinding in the overworld? That’s a pretty typical issue in older games like this. So I start marching around more purposefully, willing those monsters to appear and try to stop me.

The first monsters to do so are some beanbag-looking things on the ground. They provide almost no fight at all. If anything, I think they mostly exist to help teach players that attacking low vs. high will be important, since you need to duck to reach them. The high-vs-low attack pattern is the cornerstone of Zelda II’s combat system, and in theory, it adds a lot of nuance to fights—tougher enemies require you to block and attack in both high and low stances in order to defeat them. The problem is, there’s no windup or warning as to where an enemy is about to attack, so there’s more luck than strategy involved.

I also discover that in addition to wandering monsters, there are wandering fairies! Fairies are your best friend in any Zelda game, usually refilling your health completely. In this case, I don’t need the health—I already had it restored by a woman in one of the towns, who does so via an infamously suggestive invitation.

I see little numbers appear when I defeat enemies, so I’m getting somewhere! But I haven’t found a candle or any alternate route to the Parapa palace. I seem to recall that you just need to go through the cave with no candle, and pick it up somewhere on the other side. There’s really no other option right now, since I’ve apparently gone everywhere else that’s currently available. On the way back to the cave, I find myself in another forest battle. This one goes poorly.

Yep, the ol’ hide-offscreen-where-I-can’t-hit-you trick. The final spear hit kills me because I wrongly assume that it will bounce off my shield, but apparently I was a little too far away. Sorry, Hyrule, Ganon’s on his way back.

Thus another adventure ends unimpressively. On the plus side, the next installment marks the point at which we leave the “Nintendo hard” 8-bit era and the games start getting a lot more accessible. So I should get a greater overview of each game from this point forward.

Things I liked

- The willingness to experiment. Even if a lot of it didn’t work, I appreciate that the developers went out on a limb and totally reinvented the gameplay when they could have just chased the success of the first game with a quick set of new dungeons in the same engine. I will always admire creative work that takes risks.

- The overworld map is a nice attempt to make the world feel grander in scale. I like that you can see the monsters before you get pulled into combat, unlike a lot of RPGs.

- I was impressed with how lively the towns feel as you walk through them, a nice contrast to the lonely and post-apocalyptic vibe of the first game.

- Even though it makes little sense—they’re clearly not royal residences—I like the use of the word “palace” to describe the dungeons. In Japanese the word is closer to “temple” or “shrine” but Nintendo didn’t allow any religious references in their US releases at the time.

Things I disliked

- Not only is the game very difficult, but it gives poor feedback on why you’re not doing well. It’s very hard to improve.

- It’s often unclear where to go at any given time, and the game doesn’t really reward aimless exploration.

- Switching between overhead exploration and side-scrolling action is actually a clever idea, but the game doesn’t do much with it. Why not make the sidescrolling sections more vertically-oriented, since you can’t do that in a top-down perspective?

Was that a fair death?

Well, my inability to hit the Moblin was clearly a glitch, so that part wasn’t fair. But the spears do travel on a clear arc and I should not have been so careless as to assume that the last one wouldn’t hit me. I’m going to call this one 50% fair.

Stray thoughts

What I find fascinating about Zelda II is that the developers didn’t just push the game further toward RPG conventions—they pushed it further toward arcade-style action at the same time, with the side-scrolling view and emphasis on twitchy combat. In some ways this was incredibly forward-thinking, given that action games would eventually embrace a lot of RPG elements and RPGs would increasingly favor real-time combat. But it also took the Zelda formula away from a happy medium that it had already found in its first installment. Clearly Nintendo realized this, because they’d return to the top-down contiguous world in A Link to the Past and stick with it for all the 2D installments going forward. Tune in next time as we make the leap to the 16-bit era.