Let's Play The Legend of Zelda Series Until I Die! Link's Awakening

In which the series takes a fun detour into the weird, and sets the tone for quirky one-offs to come.

The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening

Released: 1993 (Game Boy)

I’m calling it: best Zelda opening cutscene ever. With just a few quick shots and no text, the game gives us all the context we need to jump into a new adventure. A boat crosses a stormy sea at night. Link is onboard. Lightning strikes. A young woman finds Link washed up on shore. There’s a giant egg. The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening. Boom. And all on the most underpowered hardware1 the series has seen yet!

There’s no sword in the title text this time. This little choice gives us a hint that there’s something a tad different about the experience to come. It’s still an epic adventure (and there’s still a sword and a lot of stabbing), but Zelda’s first handheld game is going to be smaller, more intimate, and a whole lot weirder than the three previous titles.

Development background

Link’s Awakening started out in the late 80s as a small after-hours hobby project for Nintendo developer Kazuaki Morita and several others. Their goal was to create an experience something like Zelda on the then-new Game Boy hardware. The results were impressive enough that the project caught the attention of Nintendo’s higher-ups, who decided to use it as a base for a Game Boy port of A Link to the Past. Eventually it became its own standalone game, with a cheeky self-referential sense of humor and a lot of weird surrealism directly inspired by Twin Peaks, of all things. Small wonder that the game would feel so singular in the Zelda canon. It’s the first game in the series to take place outside of Hyrule, and the first not to feature the Triforce, Ganon, or even Zelda herself. Its reception was good enough that it saw two re-releases over the years: a color version for the Game Boy Color in 1998, and a modern remake for the Switch in 2019.

The story

I firmly believe that in video game storytelling, less is more. So I prefer the opening cutscene in isolation. But if you really want to know why Link was at sea (and for that matter, which Link) the manual has a bit more backstory:

This is a direct sequel to A Link to the Past, so we’re playing as the same Link who walked face-first into a skeleton and died defeated the evil Ganon in his Dark World fortress and restored peace to Hyrule. In spite of this victory, Link worried that he wouldn’t be capable of taking on the next great threat to Hyrule, and so he set off on a “quest for enlightenment” to ready himself. The journey was “long and fruitful,” apparently, but we don’t find out what Link did or learned, just that his ship got owned by that bolt of lightning from the cutscene. And that pretty much brings us up to speed.

How far can I get before I die?

About 35 minutes. Once again, I am no match for the first few rooms of the first proper dungeon. I’m not (or rather, Dennis is not) even a match for the newly-restrictive name input.

Nooooooooooo

The game starts with Link waking up, appropriately enough2. The woman who found him on the beach is at his side, and she must look like Zelda, because Link seems to confusedly refer to her as such (Link is a silent protagonist as always, so we have to piece together what he says from her response). She introduces herself as Marin, and tells Link that he’s on Koholint Island. She advises him to walk south to the shore where he washed up, but to beware of dangerous monsters about. Apparently they showed up at the same time Link did, in what can only be a complete coincidence.

Ugh. Marin’s father Tarin is also in the house, and he helpfully gives “Denni” back his shield, so we can defend ourselves on our way to the shore. He speaks in a corn-pone sort of dialect, which is notable. Zelda characters rarely talk this distinctively in the English localizations. In Japanese, it’s a natural feature of the language that you can tell very specific things about a person’s background and class by their dialect, but most Zelda translations don’t try very hard to carry this over.

I step outside into Mabe Village, a modest settlement of a few houses, bouncy background music, and winking cameos from other Nintendo franchises. The Chain Chomp tied up in front of this house always makes me tense up, because in its original Mario incarnations, it would quickly try to murder me. But here on Koholint, it’s just a harmless pet, snapping away at the butterflies serenely floating around it. Zelda games will feature plenty more of these kinds of references over the years, but only in this game are they so blatant.

If the Chain Chomp cracked the fourth wall, these kids playing ball at the south end of the village are the ones who smash it by explaining how I can save my game (pressing all the buttons at once. It sounds impossible today, but the Game Boy only had four face buttons).

As I make my way to the beach, I start running into octoroks, that classic early Zelda foe. I get dinged by a projectile but otherwise make it to the water in one piece. I spot my sword lying in the surf, but before I can grab it, I am halted by Exposition Owl.

Exposition Owl will show up throughout the game to ensure that we know what our next goal is, and to ensure that we spend some time listening to him ramble even after we get the picture. His lengthy monologues wouldn’t be quite as annoying if the Game Boy could display more than two lines of text at a time. This is a recurring problem in older Japanese video games, which could display a lot more text onscreen in Japanese and tailored their content accordingly.

In this first appearance, he tells us that we must have come to Koholint to wake the Wind Fish, as that’s the only way anyone can leave the island. He doesn’t explain what the Wind Fish is, instead telling us to meet him in the Mysterious Forest north of Mabe Village. So much mystery on this little island!

The owl leaves and I’m reunited with my beloved sword. It’s not the Master Sword (the end sequence of A Link to the Past emphatically, if incorrectly, informs us that “the Master Sword sleeps again…FOREVER!”), but it’s got our name engraved on it, and despite the little salt bath it took, it’s ready for some monster stabbing.

Bam! I am the master of the beach!

The controls are a nice carry-over from A Link to the Past, rather than a return to the awkward cardinal-direction stabbing of the original game. Your sword swing makes a little arc in front of you so it’s easier to hit your foes, and it can be charged up to release a spin attack. Now that I can defend myself, I decide to do a little exploring before I head off to the Mysterious Forest. Naturally, this means cannonballing off a cliff into an open well.

The well leads to a cave, which contains a piece of heart—just what I need if I’m going to survive a dungeon for once! Unfortunately I need three more pieces before I get another heart container, so I’ll have to keep my eyes peeled.

Before entering the Mysterious Wood, I spend a little time exploring Mabe Village. The game continues to pile on the meta humor as it plays with my natural inclination to raid the chests in every townsperson’s home.

The owner of the Chain Chomp has a smaller, unchained Chomp living in an unsettling room to the side of her house.

I find the fishing minigame, but I don’t have enough money to play, which is fine by me because I find fishing boring both in and out of video games. There is a piece of heart in that pond, though, so I should probably come back later.

Mabe Village is not very large, so it doesn’t take long to explore it and figure out that more interesting things are probably happening in the place I’m supposed to be. So I hike up to the Mysterious Forest—or Wood, as Exposition Owl is now calling it.

My friend E.O. reminds me that I need to wake the Wind Fish, and also tells me that a key in the Mysterious Woods will let me enter Tail Cave, which is somewhere near where I found my sword. Simple enough!

But of course the key’s not going to be right there for the taking. I’ll have to wade through no small number of monsters to get to it. Many of them are spear-throwing Boarblins, an unwelcome reminder of the spear-throwing Moblins from Zelda II who spear-threw me to death. Still humbled by that experience, I make sure to use my shield a lot.

Event though the woods are not very large, I find them hard to navigate. Link’s Awakening does an excellent job of scaling down A Link to the Past’s sprites for the Game Boy screen while preserving their charm and readability, but the tradeoff is that each screen covers a very small area, and they’re often not very distinctive. Mentally connecting the different areas is more challenging than in the previous games. It doesn’t help that there’s a talking raccoon here who actually forces you to become lost. And brags about it.

The raccoon speaks in a corn-pone sort of dialect, which is notable. Zelda characters rarely talk…ah, I see what you did there, Link’s Awakening! This is a shrewd clue that we should pay more attention to this trickster raccoon if we’re ever going to find the key we’re looking for.

I wander around, find a cave I can’t get through yet, get hit by some spears, and have my health restored by one of the ever-helpful fairies. I remember there’s a witch somewhere around here who has something that can help me, but it takes me a while to find the right path. And right in the middle of the path, the game presents me with a dirty trick. A dirty trick I really should have remembered from my first playthrough, but I don’t.

What looks like an easy, slow-moving enemy in my way…

…is, in fact, a walking novelty buzzer that shocks me as soon as my sword hits it. This feels just a tad unfair, given that I have so little room to pass by it and no indication whatsoever that I should think twice about hitting it. I probably wouldn’t care so much if I wasn’t trying extra hard not to die, but still, it seems unusually sneaky for this series.

On the plus side, I found the witch! I mean, who else would live in this spooky dead tree? I like how the design here, with one big tree flanked by smaller dead trees, hearkens back to the first dungeon from the original Zelda.

The witch tells me I have to find a toadstool. Cool. I haven’t seen a toadstool yet in my wanderings, even after covering the Forbidden Forest/Wood multiple times due to a lot of unintended backtracking. But I’m sure it’s around here somewhere.

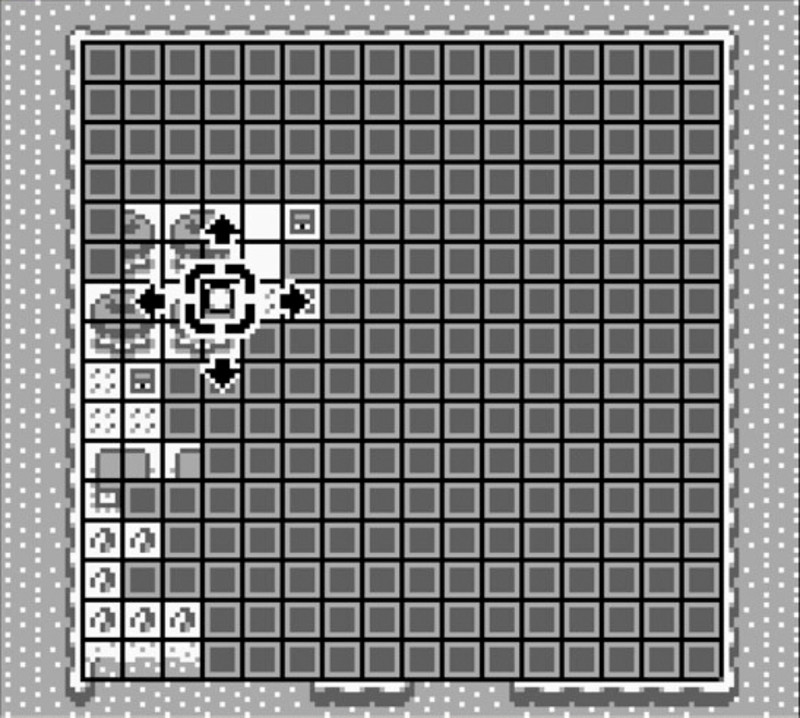

The world map is a fantastic example of minimalist design. But it’s not much help.

I decide to head back to the village, just in case one of the townspeople might have new dialog indicating where the toadstool can be found. Marin does not, but she does regale me with a rendition of the game’s most lovely and haunting musical track, The Ballad of the Wind Fish.

The rest of the town is of no help, and they don’t even sing for me. Instead they continue to break the fourth wall, telling me how save games work and alluding to future plot events. It’s cute, but right now it’s not very helpful.

I roam back to the shore in case I missed something, try to figure out if there’s another area I can access (there isn’t), and finally I decide to try the impassible cave I entered earlier. It turns out I was mistaken—I assumed I couldn’t get through the cave because it’s full of skulls that are too heavy to lift until I get some item later on. But the rounded boulders are, in fact, light enough for Link to push them out of his way. I spend an embarrassingly long time with this simple puzzle before I finally see daylight again and lay my hands upon the toadstool.

I realize I’ve now played for a while without actually entering a dungeon. This will be a theme throughout the game, which makes up for its relatively small world map by really packing in the side content.

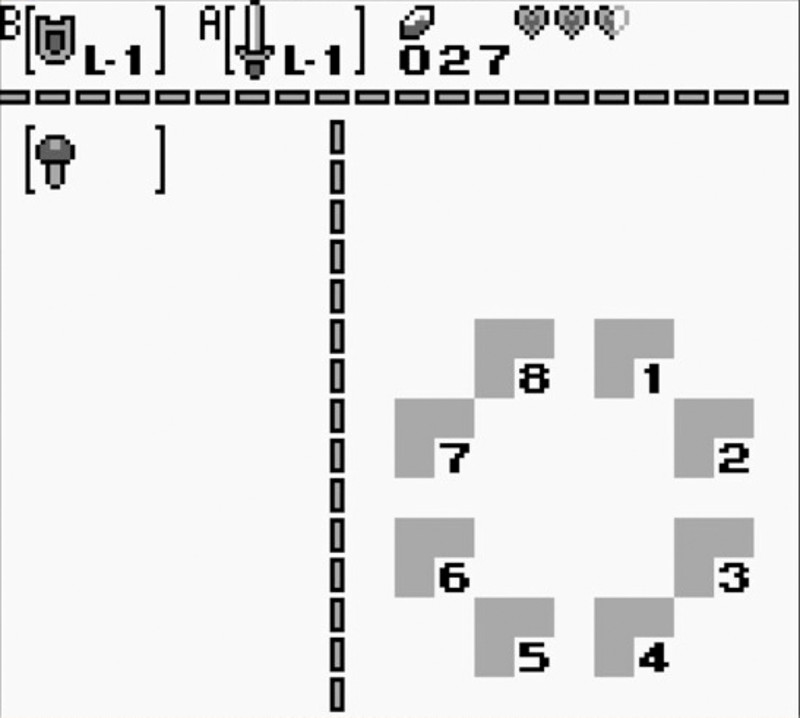

I make my way back to the witch’s treehouse, avoiding the Buzz Blob on the way, and attempt to give her the toadstool. That act requires a brief struggle with the item select screen, which is more flexible than in previous games—you can actually swap out your sword for an item, a new feature that will only be carried forward in the mobile entries. This makes Link’s Awakening particularly notable, because it reflects a split into two tracks for the Zelda series: the classic 2D gameplay will continue on handhelds, but the headlining console entries will soon be making the jump to 3D and never looking back.

With the Magic Powder in hand, I make my way back to the good ol’ boy raccoon and throw some right in his face.

He responds by spinning wildly around the screen and bouncing off the scenery like a pinball, before poofing back into human form. He reveals that he ate a toadstool before turning into the raccoon, although he only remembers this as a dream.

I figure he must have the key that I need to get into Tail Cave, but no matter how many times I talk to him, he just keeps complaining about how tired he is. When I head back to Mabe Village to see if he’ll help me there, he’s already asleep in bed.

It takes me far too long to figure out that I just needed to walk north from where I restored Tarin’s humanity to find a chest containing the key. In that time I visit nearly every other screen that’s accessible to me. I don’t know if it’s just me or not, but as much as I love Link’s Awakening, I really can’t find my way around in this game.

Naturally Exposition Owl shows up to delay me further once I’ve got the key, but I quickly escape his ramblings and head back to the coast. There, I place the key in a shrimp statue and the locked door to the dungeon opens dramatically before me.

Ok, I did it. I made it to a dungeon. I am focused, ready to plumb the depths of this monster-ridden place for the secrets hidden within. And I am not going to get killed right away, so help me Goddesses.

The first room I enter contains Hardhat Beetles, crafty foes who can’t be harmed by my sword but can be shield-bashed into the large holes in the floor along the walls. I can easily fall into those holes as well, so I have to position myself carefully to prevent my own offense from knocking me back to my doom.

Taking them out gives me a key, which opens the door to a room with the Compass. This room is also ringed with torches that shoot fireballs at me while I’m trying to fight off enemies, so I’m a lot worse for wear by the time I leave. I make my way back to the cave entrance, head north, and I find myself in a room with a curiously-shaped hole in the floor. Another Hardhat Beetle is waiting for me next to a significant-looking button.

Denni doesn’t make it to the button.

Once again, I seem to be able to handle most Zelda adventures right up until I enter a proper dungeon, and then it’s lights out. Have I always died this frequently in these games? Since I’ve never tried this permadeath approach before, and the games are pretty forgiving with their handling of death, it’s possible I just never noticed how much the early dungeons wail on me.

Things I liked

- It’s weird. I love weird. High fantasy can be a very self-serious genre, so it’s fun to see Zelda just goof around with its own conventions and have a sense of humor about itself.

- So much work went into making Koholint Island feel like a real, living place. Everything from the quirky characters to the quest structure to the tiny animations of butterflies is a part of this effort. The island is a joy to explore.

- The graphics and sound are fantastic for a handheld game from the early 90s. Nintendo had really learned their own hardware by this point.

- I’ll say it again: that opening sequence is masterful. Making a short game, or movie, or comic? Study it.

Things I disliked

- Getting lost. It’s just not fun to keep ending up on the same screens over and over when you don’t want to.

- The slow text crawls start to get really annoying after you’ve seen the same message a dozen times. Especially when you get the power-ups like the Guardian Acorn; I should be excited because I got something cool, but instead I’m irritated because I have to scroll through the full description of the item again.

- “Denni.” Come on, we couldn’t have one more letter?

Was that a fair death?

I guess so, although I’m still surprised it took off a full heart for one hit. I was trying to run away to get more space between me and the beetle and I underestimated its speed. This is becoming a bit of a pattern; I’ll try to remember to really stay focused on my foes as I take on the next games in the series.

Stray thoughts

This is it: the last Zelda game before the big shift to the third dimension. It’s the closing of an era, and as such, you can look back at these first four titles and see a microcosm of the series to come. The spirit of adventure, the freedom of exploration, the immediacy and danger of combat, the quiet contemplation of engaging with puzzles—all the good stuff is here. Of course, so is much of the bad stuff: the occasional confusion about its own core appeal, the excessive hand-holding, the overly manicured experiences, the weird little design decisions that stand out as frustrating because everything else is so pulled off so smoothly.

But really, if you excuse the roughness of Zelda II as well-intentioned experimentation (which I do), there’s precious little that these early games did wrong. By this point, they had firmly established a game experience that no imitator would ever quite match—although many would try. And only in one case did these imitators actually have the legal rights to make their own Zelda games. The results would be…well, you’ll just have to see for yourself. Next time, we’ll take a detour from the canonical Nintendo productions and check out the infamous Zelda triforce produced exclusively for the Phillips CD-i. If you don’t hear from me in a month, send Link.

-

Not really true. The Game Boy may have had a more limited color palette and a smaller display, but it had a faster processor than the NES, more RAM, and a better sound chip. Still, I think it’s highly impressive what the developers were able to deliver for this opening sequence. ↩

-

Zelda games absolutely love to start this way, so we’ll be seeing plenty more of it. ↩