Let's Play The Legend of Zelda Series Until I Die! Introduction

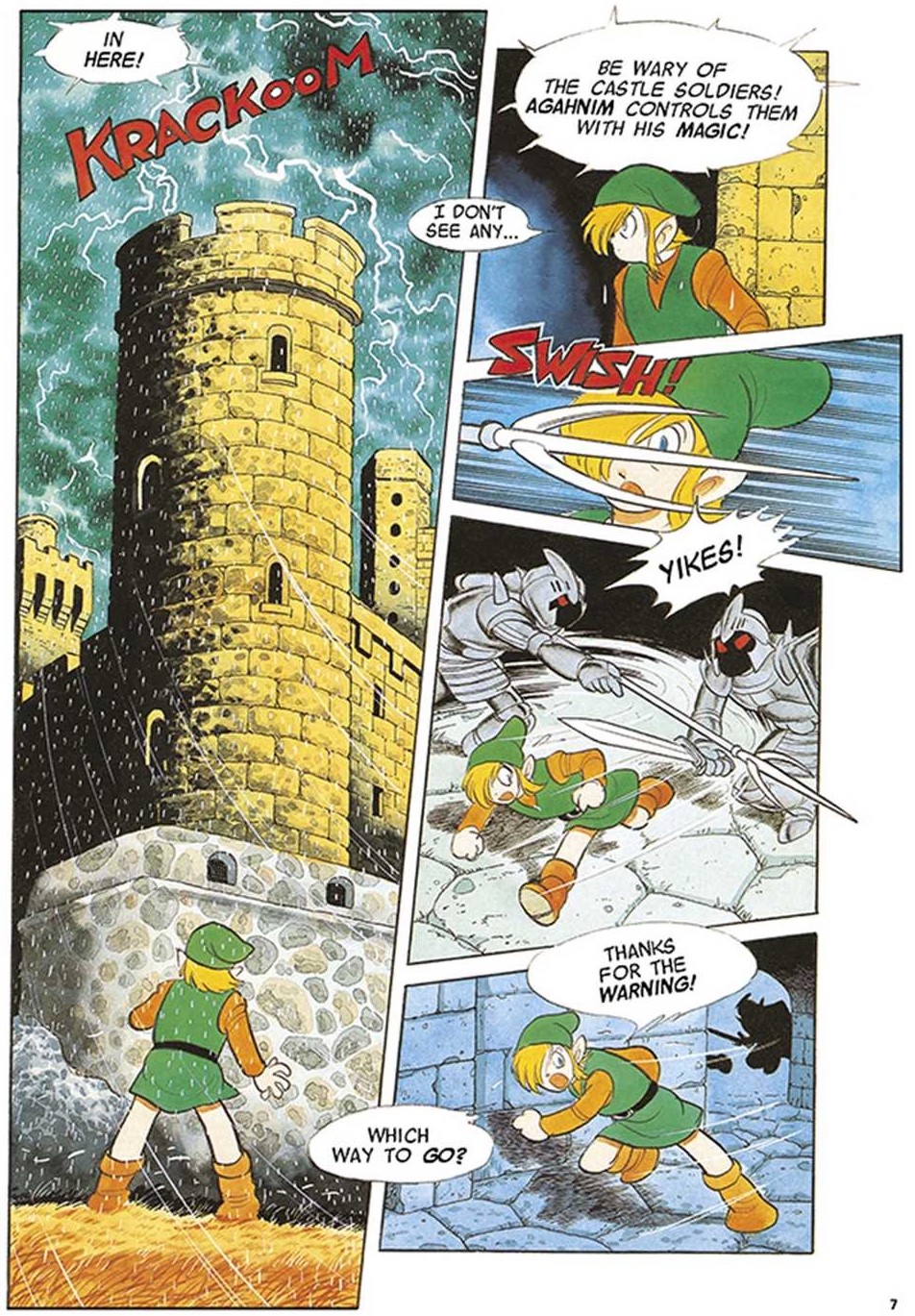

The Legend of Zelda had me hooked years before I even played it. My family owned an NES, but no Zelda, and when the 16-bit generation arrived at the beginning of the 1990s, we ditched Nintendo for the sleek, black, blast-processing allure of the Sega Genesis. That was a decision I would later regret (even if we did get to see actual blood in Mortal Kombat, very important for the discerning 10-year-old player), and the seeds of that doubt were planted as soon as I opened my friend’s copy of Nintendo Power magazine to find Shotaro Ishinomori’s incredible comic adaptation of A Link to the Past.

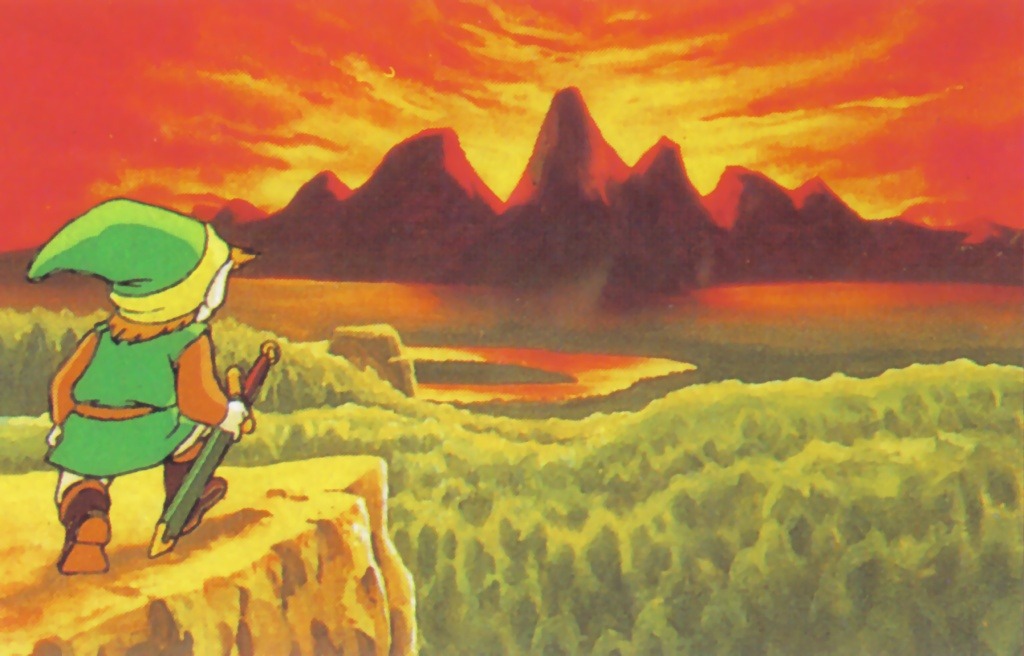

I had spent a lot of time stomping around the Mushroom Kingdom in the Super Mario games, but Link’s adventure through Hyrule seemed impossibly huge and epic by comparison. And amid the battles with giant monsters and the sweeping vistas of mountains, forests and deserts, there was a tantalizingly dark edge to the story too: Link’s uncle dies at the hand of the villain, Princess Zelda is rescued early only to be promptly magicked away, there’s an entire alternate world of darkness where your very emotions can transform you into a beast if you’re not careful. Even when Link defeats the evil wizard Agahnim, the victory is an illusion, because the real villain is a much older and more powerful foe waiting in the shadows. That kind of plot twist would eventually become rote in the series, but to pre-teen me? This was mind-blowing stuff. Just how deep was the world of these games? How far could you dive into this rabbit hole?

In 1998, I finally found out, when my brother and I got a copy of Ocarina of Time for Christmas. That game’s Hyrule was an immersive three-dimensional world that lived up to nearly all of my expectations. I spent countless hours searching temples, villages, and lava caves for pieces of heart and Gold Skultullas, and in those pre-Youtube days I would replay the epic final battle with Ganon every few months just so I could watch the ending credits again. A few years later Majora’s Mask fired up my imagination even further, with its intricately detailed world, terrifying mask transformations, and of course the iconic apocalyptic moon. The surreal surprise of entering that moon and finding a sunny field with one tree in the center, ringed with masked children, remains one of my favorite moments in all of video games.

That’s the thing so often overlooked in discussions about the Zelda games: they’re weird. Even the ones that aren’t Majora, which take place in Hyrule and follow the typical patterns of element-themed dungeons and a big battle with Ganon in the end, are much stranger than we give them credit for. They’re rooted in a very generic vein of Western fantasy, sure, all European fairy tales with castles and princesses and swords. Fantastic creatures straight out of C.S. Lewis have quirky conversations with you while you head off to fight the great world-ending evil straight out of Tolkien. But something—maybe the Japanese authorship, or the particular constraints of video game storytelling, or a combination of both—gives it a flavor all its own, one that has persisted through the series. And it’s not just goofy motifs like a guy in a green bodysuit selling you maps or seemingly innocent chickens that will destroy you if you mess with them. It is this: Zelda absolutely nails the feeling of being a child just before adolescence. These games are all about stepping tentatively onto the threshold of a grown-up world that you don’t understand and don’t necessarily want to.

Critically, though, they never quite cross the threshold. Victory is always about holding onto the status quo for a little bit longer. Ganon is defeated, but we know he’ll return someday. Link becomes a child again. Hyrule stays buried under the ocean. The gateway to the Twilight Realm is closed. Koholint Island vanishes and leaves Link adrift on the sea. We’re back where we started, and we’ll go about our life like before, but we know it’ll never be quite the same.

I think it’s for this reason that I’ve stuck with the series for so long. It’s also for this reason that the old games remain so re-playable. What could be more relatable, at any point in adulthood, than the feeling of standing right before a big scary challenge that you’re completely unprepared for? At least in a Zelda game, I can do so with a boomerang and a magical flute on hand.

It’s 2020, the untitled sequel to the landmark Breath of the Wild still has no release date, and things are…a little weird, let’s just say, and annoyingly short on problems that can be solved with boomerangs. So I think it’s time to revisit the entire Zelda series. But as I mentioned earlier, I’m an adult now; I have two children and very little free time. So, rather than try to play through every game all the way through, I’m going to do a bit of a speed-tour: I’ll play each game until I die, i.e. I see a “Game Over” screen. I think this will allow me to experience each installment long enough to appreciate its unqiue charms, and as a bonus, I’ll have an incentive to play the easier installments really recklessly.

Along the way, I’ll talk a bit about the history of each game, how it fits in the broader scope of the series, and nitpick all the little things I don’t like. You know, standard video game blogging stuff. I hope you’ll join me on this journey of more than three decades of iconic video games, beginning with the 8-bit adventure that started it all.